The Value of Experiments

Part One

“Every year is an experiment.” The wise words of Netflix’s CEO, Reed Hastings, come to mind when I think about what it means to perform experiments. Irrespective of who you are—a designer, product manager, or whatever, you just have to agree that experiments are a crucial part of the product design process.

Why? I believe Reed was referring to the constant evolution and unpredictability of the market. The digital environment changes rapidly so tweaking, testing and experimenting constantly is now a necessity.

But what does it really mean to perform experiments? I’ve reached out to four industry leaders to get their take on the value of experiments.

- Ellen Chisa, the VP of Product at Lola, a Boston-based company that provides on-demand travel services for things like hotels and airfare.

- Daniella Patrick, an Innovation Lab Product Manager for Accenture, an information technology consulting firm.

- Jordan Bergtraum, a Management Consultant, who previously worked as the VP of Product Management at ServiceChannel.

- Nis Frome, the Co-Founder, Product Manager, and Content Lead for Alpha.

With the support of a presentation deck I created, I invited these remarkable individuals to discuss what it really means to perform experiments. During our conversation, we tackled these four questions:

- What does it mean to perform an experiment?

- How do we communicate the value of experiments?

- What can experiments do for designers?

- What will users gain from experiments?

This article summarizes the discussion around the first two questions and we’ll publish the final two in the second part of this series.

What does it mean to perform an experiment?

I believe performing an experiment means validating an idea. The main objective is to see if a decision about a product is capable of pushing a business in the right direction.

Does it make sense? Will your users get it? And not only get it, but be spurred to share it and bring in new users.

Like I said earlier, I wouldn’t want to make a decision solely based on my belief. Nis was all too eager to be the first person to explore this question so I gave him the lead.

Nis referred to the Hastings’s quote about every year being an experiment. Nis believes that what the Netflix CEO was referring to could be deeper and more complex than that. To him (Nis), every day, or even every hour, is an experiment. “The market is always changing, and experimenting helps to keep your finger on that pulse and keeps you ahead of the curve so your competitors don’t pass you by.” Nis said to bolster his point.

He believes being in the right mindset is an important aspect of experimentation. Companies have to know what product to build because they do not always have the time or resources to build the wrong product.

Product or feature experiments mirror the scientific method—form a hypothesis and then find ways to prove whether that hypothesis is right or wrong. In the product space, Jordan defines it as “trying to find a cost-effective way to identify, before it is expensive, what the best opportunities for our companies are when it comes to our products.”

Does the size of the company matter?

Jordan doesn’t think so. The size of the company may affect the urgency of the experimentation but not the actual process and role. Smaller companies don’t have the resources to afford failure OR delayed delivery so they might take the experimentation process more seriously.

Remember when Instagram abruptly pushed an update to horizontal scrolling? It was momentary—rolled back within minutes—but the user pushback was nearly universal. An experiment or just a clever ploy to get people talking?

Testing Assumptions & Ideas

Daniella thinks that “Experimenting is about testing your assumptions about your product and services that you either already provide, or are considering providing.” You are able to identify weaknesses, strengths, and even new ideas which you didn’t see before.

What I especially liked about Daniella’s response was the part when she talked about how in addition to test products, experimenting can also be used to test a company’s service provider and business. Ellen took a different albeit immensely meaningful approach. She sees experiments as an extension of curiosity. “It’s all about testing the right ideas” rather than every single idea you come up with. She’s devised an agile approach to ranking ideas so that time and resources are not wasted.

She uses a research backlog to keep and organize all the ideas her team comes up with. She prioritizes them and determines whether or not they readily have the tools needed to test them. This way, you avoid wasting time and resources experimenting on ideas that aren’t feasible.

Ellen stays focused on the “big picture” of experimenting rather than the individuality of each and every idea.

In terms of the prospective ideas in the backlog, do you categorize those in any way to prioritize the value of the test that might occur?

She tries to categorize her backlog in terms of what ideas are the highest risk endeavours for her company. She said she focuses on which ideas in the backlog will make the biggest material differences for her team.

The actual experimentation process can vary depending on the company, infrastructure, and access to tools and resources. We all have different perspectives on it, but we all agree on the basic concept. Take ideas and break them down to basic assumptions and test them as cheaply as possible.

Nis has seen the concept of experimentation interrupt and invigorate the culture and flow of an organization. Simply introducing the word “experiment” to a large company can have a huge impact on the company’s products and development process.

Daniella agrees and adds that experimenting helps people keep an “agile and innovative mindset,” even those with more old-fashioned ways of thinking and working. People are more open to experiments because they have much less liability.

How do we communicate the value of experiments?

Where do you stand on the concept of having two of the following aspects of a product or experiment, but never all three: cheap, quick, and quality?

Ellen thinks it depends on how those three terms are defined. While the concept is valid in many situations, the “cheapness and speed of an experiment are what give it quality.”

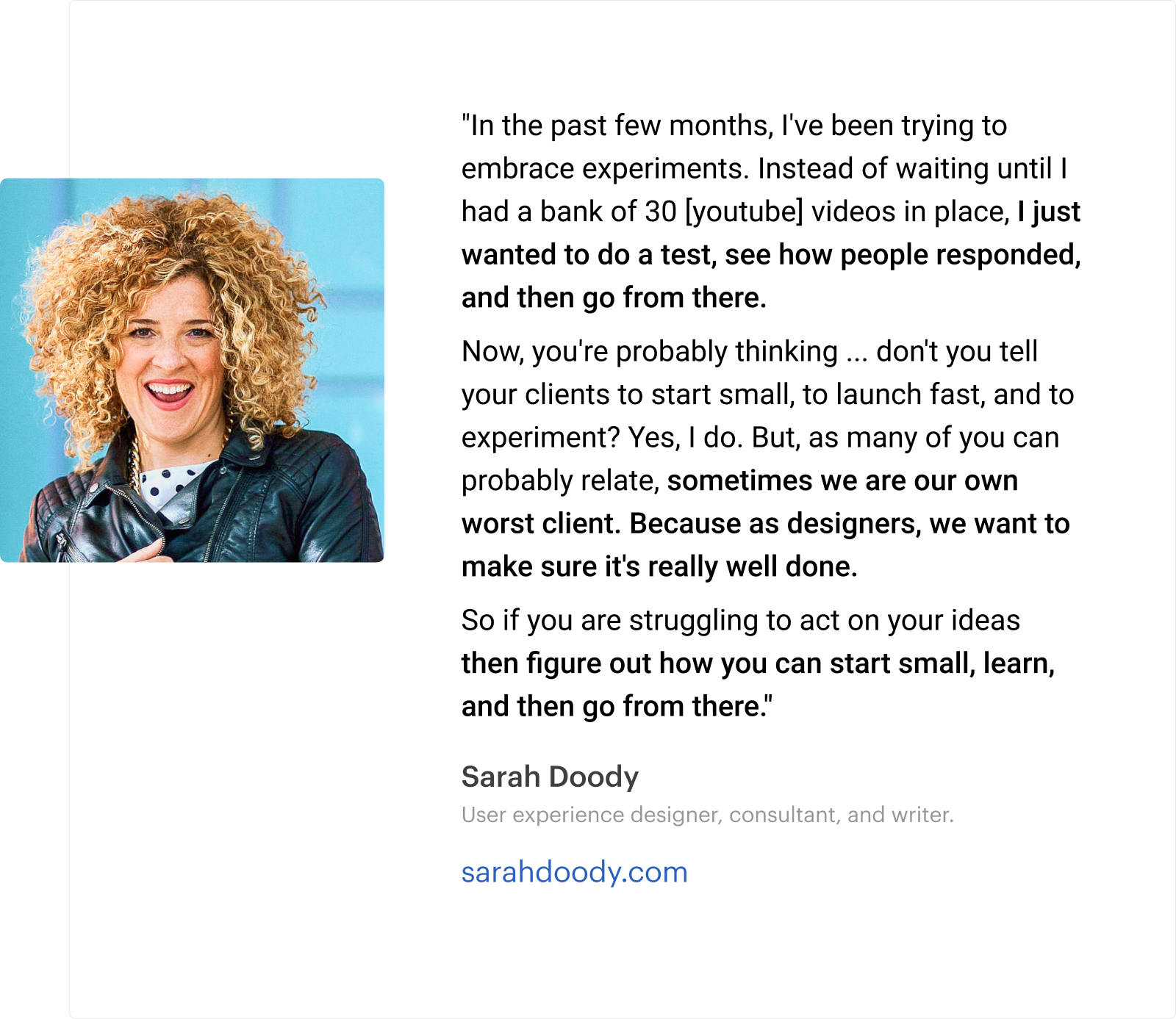

I appreciate Sarah Doody’s take on kickstarting the experiment process. “Figure out how you can start small, learn, and then go from there.”

There is really no right or wrong way to conduct an experiment. You can begin by trying something new, see how people respond, and decide where to go from there.

Daniella, as a designer, expects and strives for her experiments and products to turn out perfectly. But in the real world, there is hardly ever enough time and resources to bring that to fruition. This is good because it pushes and forces her team to “adapt, prioritize, and overcome a number of challenges.”

To Ellen, it is very important to have a clear core value proposition. Knowing exactly what problem(s) your product solves for your current and potential users will naturally guide experiments in the right direction. If you start compiling a history of experiment results that support your core value proposition, leadership will quickly see the value.

Jordan believes that experimentation is about getting feedback and testing rather than perfecting. His company’s clients run around 250 experiments monthly. Carrying out the experiments isn’t the biggest challenge they face. The main obstacle is reverting to perfectionism rather than staying in the agile test-adapt-test mindset.

For example, a client wanted his company to run an extremely long study that they had spent a lot of time and resources developing and writing out. After the three month study, they discovered that their users didn’t understand the terminology they were using. So, rather than simply testing the terminology quickly, they wasted three months and did not get useable results.

I see a lot of hesitation when discussing experiments with clients. But there is less when it comes to getting user feedback because most clients recognize the importance of it. Once you begin to notice a pattern with your results, you have successfully conducted your experiment and can proceed to make conclusions.

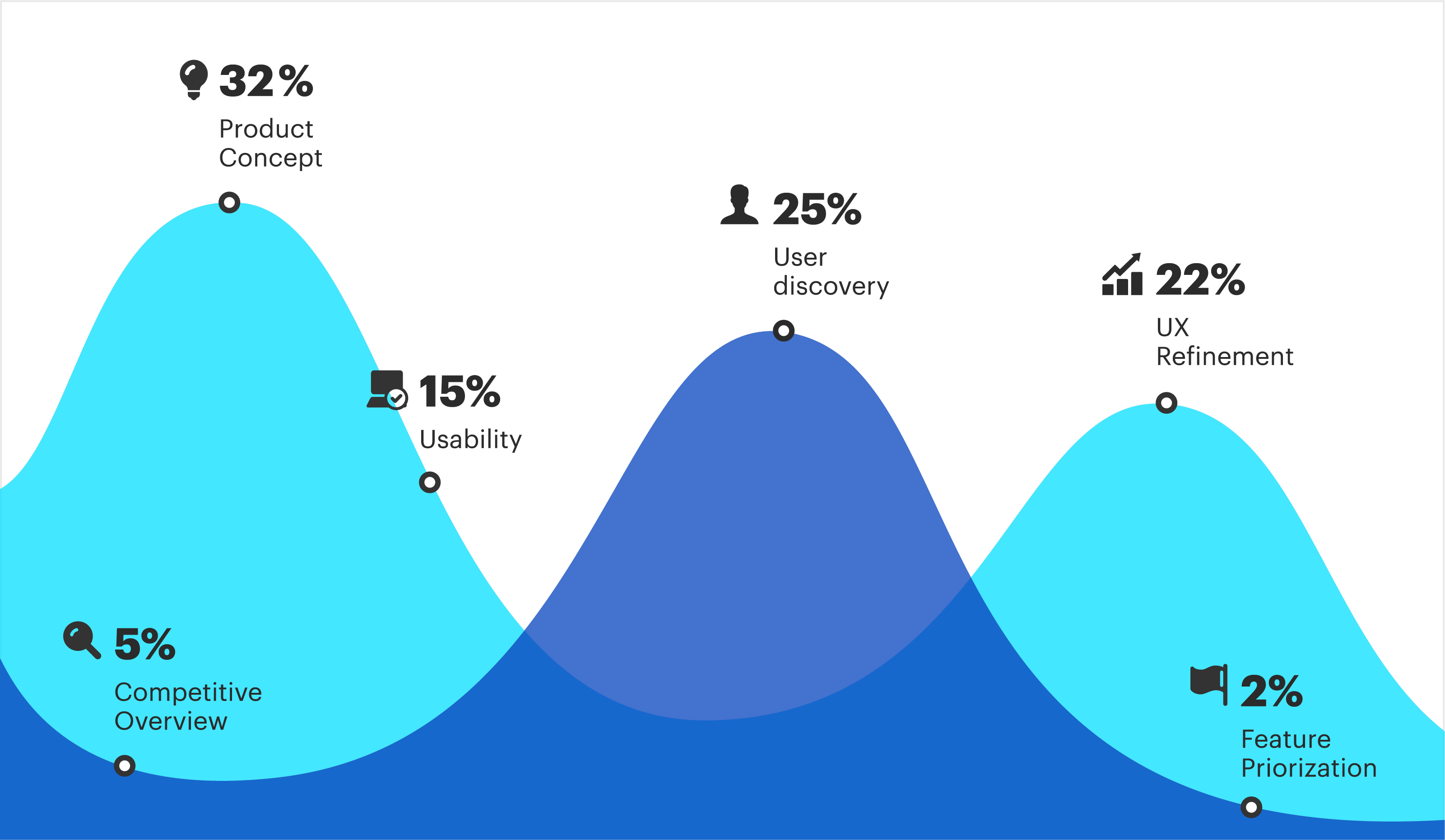

Next, I referred to a statistics on the frequency of different types of experiments. The statistics showed that product concept, user discovery, and UX refinement experiments are the most common.

Nis thinks high level idea experiments are the most common as they occur at the very beginning of the development process. They determine which ideas are worthwhile and which should be scrapped. After a core idea takes shape with a clear value proposition, you can then proceed to conduct the smaller refinement experiments.

He believes product concept experiments are the most important. They significantly limit risks and costs of failure. Skip these and you should be prepared to spend over a million dollars on a product that users do not want or need.

Daniella adds that it is extremely important to be proactive. It is easier and more cost effective to think of an idea, confirm the market fit, and bring it to life.

Ellen sums it up perfectly.

As a company leader, you have a responsibility to your team, your stakeholders, and your users to be proactive and build the best product, rather than the better product.

…

Experiments are a key tool to meeting that responsibility.

In part two if this series we discuss the benefits for designers and end users.